How Does an Automatic Movement Really Work?

It’s a silent dance you wear on your wrist. An energy born of your movements, passed from one piece of metal to the next, regulated to the hundredth of a millimetre to display the correct time. An automatic movement is nothing magical — it’s a mechanical art, heir to three centuries of ingenuity, made of masses, springs and rhythms. Here is, without mystery, how it really works.

An invention born of motion

In the 18th century, Abraham-Louis Perrelet devised an oscillation-winding system for pocket watches. But it was on the wrist that the idea would truly flourish. In the 1920s, John Harwood filed the first patent for an automatic-winding wristwatch. Then, in 1931, Rolex established its freely rotating 360° rotor — the famous “Perpetual” — which would become the grammar of the genre. The following decades refined efficiency: Felsa invented the Bidynator (bidirectional winding) in 1942; Seiko popularised the Magic Lever in 1959, a simple, robust solution. The automatic was then ready for modern life.

A video that explains a watch movement

You have to like Tchaikovsky (which I do) and add the rotor to the equation

The path of energy: from wrist to hand

1. The oscillating weight and the winding train

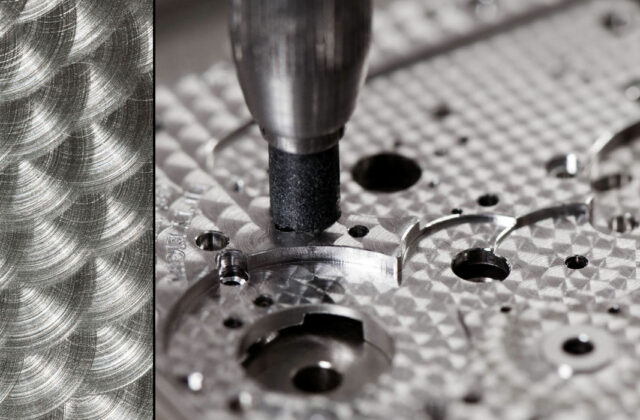

On the back of the movement, a half-moon mass — the rotor — pivots around its axis, often mounted on ball bearings. Wrist movements make it swing; its weight (tungsten, 18- or 22-carat gold) provides inertia. The rotor transmits this motion to a set of wheels and pawls: the winding train. Depending on the design, energy is captured in one direction (unidirectional) or in both (bidirectional via “reversers” or a two-armed Magic Lever that grips the back-and-forth). The goal: to convert random gestures into efficient winding.

2. The barrel and the slipping bridle

This winding tensions a mainspring housed in the barrel. To avoid any destructive over-torque, the last coil of the spring features a slipping bridle: it grips the barrel wall by friction and slips when maximum tension is reached. The result: you don’t “break” an automatic by wearing it too much; excess energy is dissipated by slipping, elegantly.

3. The gear train, escapement and balance

Energy leaves the barrel through a cascade of reduction wheels (the gear train) to the Swiss lever escapement. There, motion is chopped into regular impulses, which keep the balance and hairspring oscillating. This is the beating heart: its frequency — 21,600, 28,800 or even 36,000 vibrations per hour — sets the tempo; its amplitude, the health of the regulation. The hairspring, preferably in silicon, breathes, the balance oscillates, and each impulse releases a step, turning the hands at exactly the right speed.

An art of solutions: unidirectional, bidirectional, micro-rotor

Each manufacture chooses its own school. Unidirectional winding limits losses and simplifies the architecture; bidirectional winding maximises energy capture in the city as well as at the office. The Magic Lever, prized for its robustness, delivers remarkable efficiency with few parts. Others make thinness a manifesto: the micro-rotor, recessed flush with the mainplate, allows for slimmer movements, elegant under a cuff. The peripheral rotor, a ring around the edge, frees the view of the movement and lowers the centre of gravity. In every case, aesthetics converse with mechanics: openworked gold masses, Geneva stripes, guilloché… technique becomes decoration.

Accuracy and consistency: what happens inside

A well-designed automatic movement targets both power reserve (40 to 80 hours, sometimes more) and stable rate. Accuracy depends on fine regulation (index, inertia blocks, a silicon hairspring to limit magnetic sensitivity), lubrication quality, and amplitude. Shocks? Anti-shock systems such as Incabloc or KIF protect the balance pivots. The best meet chronometer standards (COSC, -4/+6 s/day) or in-house variants. And because life isn’t a display-case watch, hacking seconds for atomic-time setting and supplementary manual winding remain real comfort features.

Misconceptions to forget

- “I don’t move much, my watch will stop.” A normal daily routine is enough. If you’re very sedentary, 20–30 crown turns in the morning will stabilise the reserve.

- “You can overwind an automatic.” The slipping bridle protects it: no breakage from excessive winding.

- “A watch winder replaces servicing.” No. It keeps the watch running, not the oils. Periodic servicing is still necessary.

- “Magnetisation = the end of the movement.” Often reversible in a minute with a demagnetiser; silicon hairsprings are almost insensitive to it.

- “A mechanical watch must be perfect.” Look for a reasonable drift that is stable and repeatable, rather than absolute zero.

Use and care: the practical truth

An automatic likes to be worn. One to two days of movement will pace its power reserve. Alternating it on a winder can help if you have calendar complications, but it isn’t essential.

On the care side, the golden rule is consistency: a water-resistance check every year if the watch sees water; a service every 5 to 7 years depending on use, to replace oils and gaskets, check wear on pivots and jewels, and clean the gear train and escapement. Avoid strong magnetic fields (loudspeakers, case clasps, industrial gates), rinse with fresh water after the sea, and handle a screw-down crown with delicacy. When it’s on the table, vary its position at night: some watches gain or lose differently “dial up”, “crown up”, which can help you fine-tune drift empirically.

Why we love them: beyond the technical

- The sensation: the rotor’s gentle back-and-forth, an intimate wink from living mechanics.

- The beauty: a micro-rotor that opens up the view of a mirror-polished bridge; a 22-carat gold mass, engraved and weighted for superior efficiency.

- The culture: from the 1931 “Perpetual” to the Magic Lever, each solution tells of an era, a workshop philosophy.

- Durability: no battery to replace; an ecosystem of replaceable, serviceable parts that spans decades.

As a final second

An automatic movement is a happy compromise: capturing life’s randomness and converting it into measured time. A weight that turns, a spring that tightens, a balance that breathes — and suddenly, your day finds its cadence. In this mechanism there is intelligence, the hand, and a little poetry. Every gesture winds you; every second resembles you.