How Does a Mechanical Watch Work?

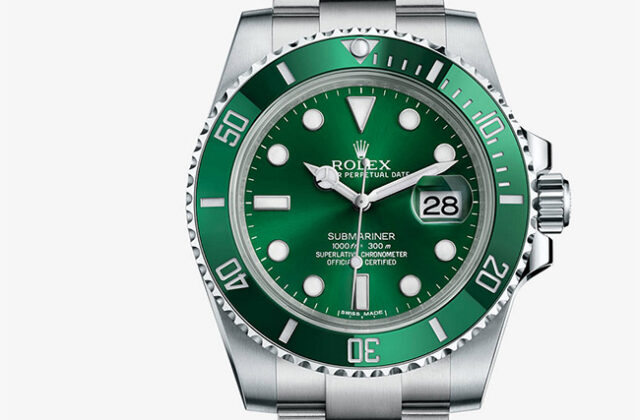

What mechanical-watch enthusiast has never heard: “A watch without batteries?! Like a Rolex,” a little line that, first, reminds us of some people’s lack of knowledge of watchmaking history and, second, of the overwhelming fame of the brand with the crown.

The aim of this article is to try to popularise the technical side of our mechanical timepieces, while also addressing the historical dimension of the various innovations that have gone hand in hand with the evolution of watchmaking. A tough task, making digestible content that would make any student on a watchmaking course go pale.

The first mechanical watches were born around the same time as the advent of the mainspring. Man had already been building mechanical clocks as early as the 13th century; their driving organ was a weight swinging at the end of a cord. Hard to miniaturise such a device and integrate it into an object some fifteen centimetres long that could fit in a pocket.

The invention of the spring and its technical characteristics would change the game. Around 1450, it was realised that the spring’s capabilities could be used as a driving organ for new portable timekeeping instruments. In 1482, the first “sautoir” watches appeared at the court of the Duke of Milan.

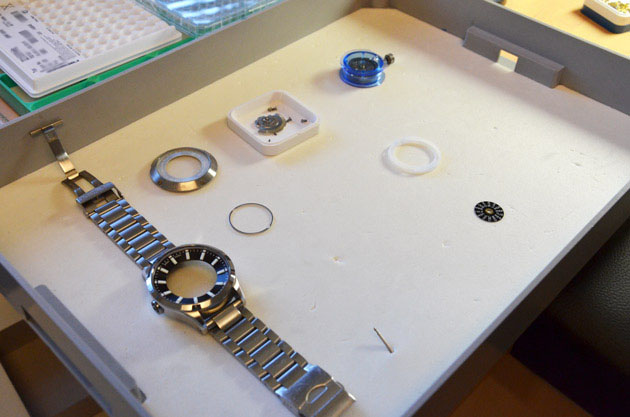

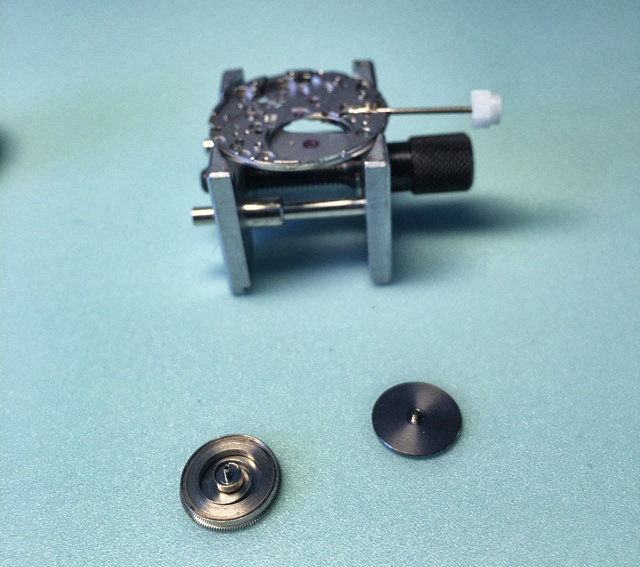

The spring is considered an energy accumulator. The energy source is the sun, enabling the watch’s user to wind this spring (housed in a closed cylinder called the barrel) via the winding stem and the crown.

When winding the watch, the spring coils around the barrel arbor. Once winding—also called “arming”—is complete, it will try to return to its original shape, producing the energy required for the watch to run. This energy is transmitted to the gear train via teeth on the barrel.

That, in simplified terms, is the role of the first of the five organs required for a mechanical watch to function properly: the power source.

Technically speaking, by operating the winding stem we transmit force, via pinions and intermediate wheels, all the way to the spring housed in its barrel.

So we’re well on our way with our spring fully wound—but how can a mechanical force possibly count our precious time and indicate the hour?

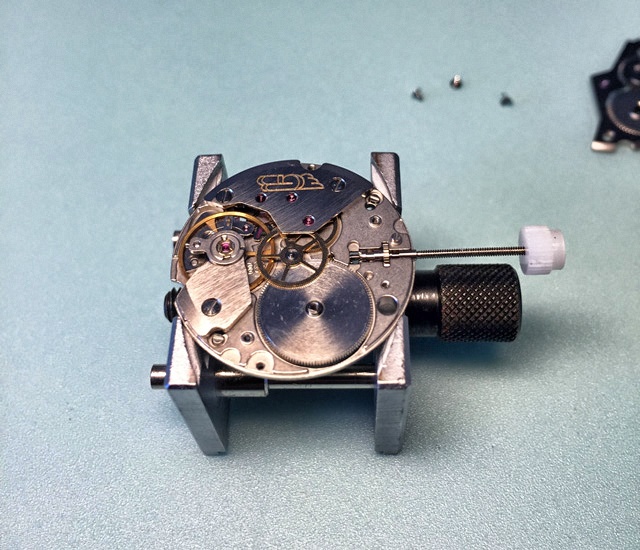

It is at this precise moment that the role of the watch’s famous wheels truly comes into its own: the counting and transmission organs.

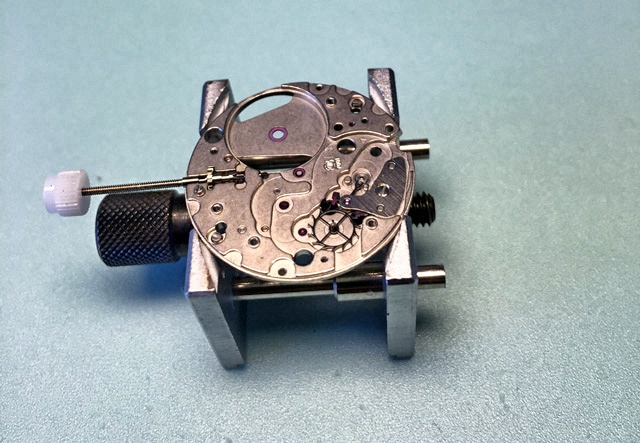

Through an ingenious system of wheels and pinions, the force is counted (mathematical ratios: number of teeth/diameter/time) and transmitted to the distribution organ.

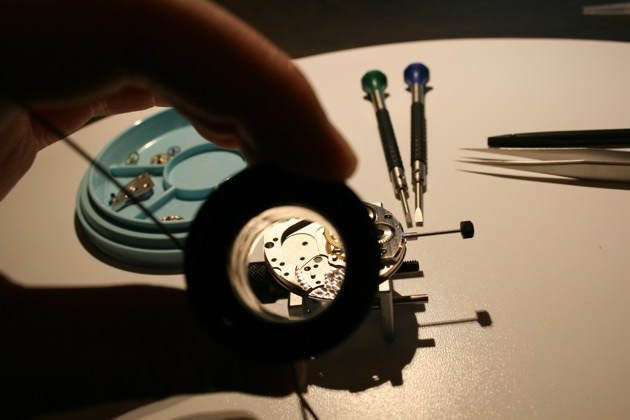

Most often, these moving parts are hidden between the mainplate (the body of the movement) and the bridges that hold this whole little world in place.

We are already a little further along in understanding our mechanical movement. From the crown we have reached the end of the gear train, and now we come face to face with the escapement: the distribution organ.

The escapement was invented by the Dutchman Huygens around 1660—the same inventor who created the balance spring in 1675, but we will come back to that later.

The first escapements were designed to maintain the motion of the pendulum (a weight at the end of a cord) in mechanical clocks. The same function was adapted to portable instruments.

There are different types of escapements: recoil, frictional rest, and free. The first two were abandoned because too many contacts and too much friction interfered with the watch’s accuracy.

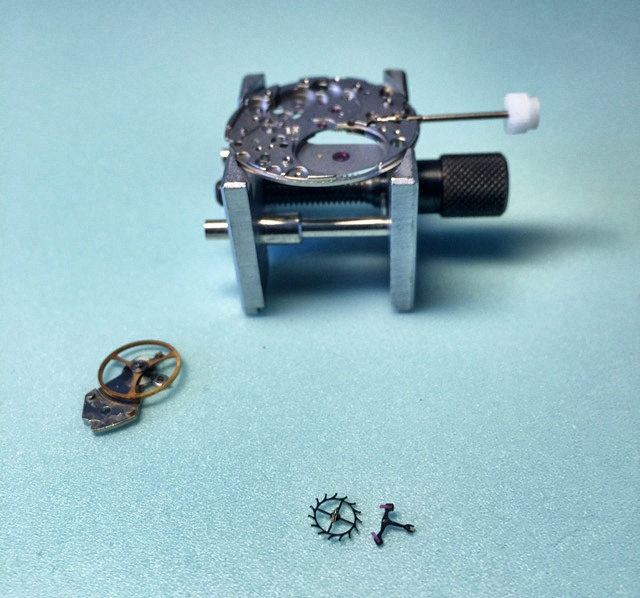

The Swiss lever escapement (a free escapement) is currently the most widely used. It consists of a wheel (the escape wheel) connected to the gear train; a pallet fork that interacts with the escape wheel via “pallets” made of synthetic ruby; and a double roller fitted to the watch’s balance staff.

The concept of the escapement is a little difficult for the novice to grasp: it makes it possible to interrupt the motion of the gear train at regular intervals and to distribute, periodically, the energy required to sustain the balance’s oscillations.

Put more simply, it allows the force coming from the barrel to be cut off at a given moment, and then returned at the desired moment to the regulating organ (the balance and hairspring).

As we saw earlier, it was Huygens who invented the hairspring in 1675. This hairspring would be paired with a balance to become the regulating organ of almost all mechanical timepieces.

It is an oscillating system composed of a balance, on the staff of which a hairspring—most often made of Invar (an iron alloy with 36% nickel)—is attached. The material is very important in hairspring manufacturing because performance depends on it: the most constant torque possible, whatever the external variations (temperature, magnetic field, humidity, position).

It is the balance and hairspring that regulates the force coming from the barrel. Thanks to it, we can make the watch run fast or slow in order to have a timekeeping instrument that is accurate and durable over time.

There we are—we have completed our tour of the movement, trying to understand the role of each of the organs that make it up. I have deliberately not gone into detail, as that was not the purpose of this article.

Now we have an overview of the movement and its main components, which can be applied to almost all mechanical watches produced today.

We will cover the differences and subtleties of special mechanical constructions (chronograph, perpetual calendar, etc.) in a series of articles to come.