Why Some Watches Stop When You’re Not Wearing Them

The little morning drama: a frozen watch, time on pause

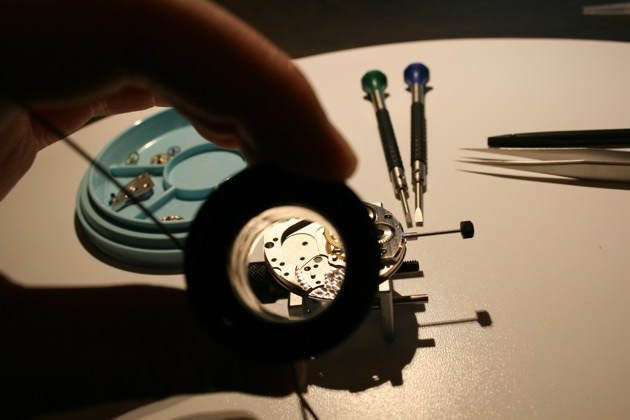

There’s that gesture—intimate, almost ceremonial: picking up your watch from the bedside table, feeling the cold metal or the mellowed leather, then realising the seconds hand isn’t moving. Everything stops at once, as if the object has decided to fall silent. You give your wrist a gentle shake, you frown, you adjust the crown. And you wonder, slightly put out: why does it stop when I’m not wearing it? The phenomenon is especially intriguing when it’s an automatic movement—a silent dance that depends on your gestures. Yes, this article is aimed at watchmaking newcomers, but what enthusiast wouldn’t enjoy reliving that moment when you first discover the difference between a quartz movement and a mechanical one?

The answer lies in a blend of simple physics, watchmaking architecture, and a philosophy of time. A mechanical watch isn’t a gadget: it’s an organism. It lives on the energy you give it, and when you stop feeding it, it naturally winds down. To extend its life and preserve its accuracy, it’s essential to know how to care for a mechanical watch day to day.

The real reason: energy is finite—and so is the power reserve

In a mechanical watch, everything begins with an energy reserve stored in a spring: the mainspring, housed in a drum called the barrel. When you wind the watch (by hand) or when you wear it (if it’s automatic), you tension that spring. It then unwinds gradually to drive the gear train, power the escapement, and keep the balance oscillating. That precision and complexity are part of the timeless appeal of mechanical watchmaking, which continues to captivate automatic-watch lovers.

But that energy isn’t infinite. It corresponds to what we call the power reserve: the amount of time the watch can run without any additional input of energy.

How long can a watch run without a wrist?

- Hand-wound mechanical watch: often 40 to 50 hours, sometimes more.

- Modern automatic watch: frequently 38 to 72 hours.

- Long power-reserve movements: 5 days, 8 days, or even more depending on the architecture.

If you leave a watch unworn for two days and it has “only” a 40-hour reserve, it will stop. That’s normal. It’s neither a fault nor a whim—just the logic of a mechanism.

Automatic vs manual: two ways of feeding the movement

The hand-wound watch: the elegance of ritual

With a manual-wind watch, the situation is crystal clear: if you don’t wind the crown, the watch stops. Many enthusiasts love precisely this ritual—a few turns each morning, the way you might straighten your tie. It’s a direct connection to the object and to a watchmaking tradition that’s several centuries old. Here’s what it looks like on video:

The automatic watch: the illusion of autonomy

An automatic watch, by contrast, winds itself thanks to a rotor: an oscillating weight that turns with the movement of your wrist. The key word is right there: movement. If the watch is left sitting still, the rotor doesn’t turn. And if you’ve spent the day in front of a computer—short gestures, a largely motionless wrist—the energy input may be insufficient.

In other words, an automatic isn’t a “watch that never stops”. It’s a watch that winds itself if your life gives it a rhythm.

Why do some stop sooner than others?

Two watches sitting side by side don’t necessarily have the same stamina. Several factors come into play.

1) A shorter power reserve

This is the most common case. Compact calibres, older movements, or certain models designed for slimness sometimes prioritise silhouette over longevity. A smaller barrel often means less stored energy.

2) A watch that isn’t fully wound

Sometimes you set an automatic down in the evening thinking it has “done its day”. But if you put it on after lunch, or if the day was sedentary, it may never have reached a full wind. Result: it stops during the night or the next morning.

3) More power-hungry complications

Some functions consume more: central seconds, big date, chronograph, additional displays, or certain calendar systems. All else being equal, the more there is to drive, the more the energy is spread out—and the effective power reserve can feel shorter.

4) Lubricants, age, servicing

A mechanical watch is a set of controlled frictions. Over time, oils can degrade, thicken, or migrate. The movement loses efficiency: the watch may then run for less time, or even stop sooner. It’s a classic sign that a service (overhaul) may be worth considering.

And what about quartz watches?

If your watch is quartz and it stops when you’re not wearing it, the logic changes. In principle, a quartz watch runs without relying on your wrist: it’s powered by a battery (or a rechargeable cell, in the case of solar models). If it stops:

- Low battery (very common).

- Power-saving mode on certain models: the hand may stop but the watch “continues” internally.

- Poor contact after a knock or moisture.

In that case, the stoppage isn’t expected “by design” as it is with a mechanical watch: it’s a signal that needs interpreting.

The watch winder: a chic solution or a false good idea?

The watch winder—half furniture, half machine—is often presented as the modern answer: it keeps an automatic watch in motion when it’s not on the wrist. It’s practical, especially for perpetual calendars or complex calendar watches that are tedious to reset after they stop.

But there’s a cultural—and mechanical—flip side. From an enthusiast’s point of view, leaving a watch running permanently can feel at odds with the very idea of a “living” watch that falls asleep. From a technical standpoint, a quality winder, correctly set (proper direction of rotation, appropriate turns per day), isn’t a problem in itself. A poorly adjusted winder, on the other hand, can keep the watch turning unnecessarily and, over the long term, wear certain parts faster.

How to keep a watch from stopping (without becoming a slave to setting it)

A few simple habits are enough.

- Give it a proper charge: if the watch has stopped, wind it (and/or wear it) before you head out. Many automatics also allow manual winding.

- Rotate intelligently: if you change watches every day, favour models with a 60–72-hour reserve… or accept the idea of setting them again, which is part of the charm.

- Check the movement’s condition: a power reserve that drops noticeably can indicate the need for servicing.

- Avoid unnecessary shocks: an automatic watch doesn’t like impacts, even if it’s robust.

What watchmaking says about us: a watch stops because it isn’t worn

Within this technical question lies an almost literary truth: a mechanical watch stops when it isn’t worn because it was designed to accompany a life. Pocket watches had to be wound out of necessity; automatics invented a kind of symbiosis—your movement creates its own. When you leave it on a shelf, it powers down without resentment.

And perhaps that’s what sets mechanical watchmaking apart from everything else: it doesn’t promise eternity. It promises continuity, as long as you’re there. Setting your watch again isn’t a chore. It’s a return to the present—a brief exchange with an object that measures time… while quietly asking you to give it a little of it.