How to Recognize a High-Quality Automatic Movement

Why the quality of a movement isn’t always visible to the naked eye

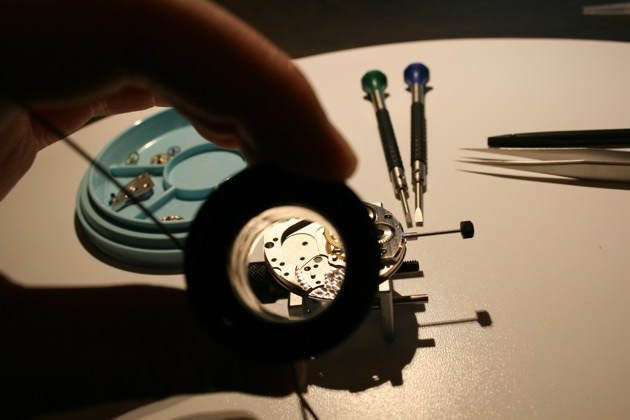

You turn the watch over; the sapphire caseback reveals a ballet of wheels and a half-moon rotor. It’s beautiful, hypnotic. But in mechanical watchmaking, beauty isn’t just a matter of reflections. Recognising a high-quality automatic movement means reading between the lines of a calibre: its finishing, its architecture, its ability to keep time—and to last. It also means understanding what marketing doesn’t say, and what old workshops still whisper: quality lives in the details, in the act of regulation as much as in polished steel.

Finishing: the grammar of beauty that works

A movement’s finishing isn’t merely decorative; it signals a level of rigour. It takes time, tools, and a steady hand. It tells you something about a maison’s culture.

- Anglage: the mirror-polished bevel running along the bridges. Crisp inward angles (internal corners) betray handwork; a machine struggles to cut them cleanly.

- Côtes de Genève: those undulating stripes born in the 19th century. They should be even, with no smearing at the edges of the bridges.

- Perlage: the pearly dots on the mainplate. Uniform density, controlled overlap: a living pattern, not simple stamping.

- Snailing and sunburst finishing: on barrels and wheels, they signal care given to functional components.

- Blued screws: heat-blued (a deep blue) rather than dyed. A detail that breathes tradition.

Be careful: a flashy laser-engraved rotor isn’t enough. Look for coherence—careful finishing even in hidden areas, countersunk screws, crisp edges. A well-finished automatic movement is a movement that has been respected by the person who assembled it.

Architecture and materials: quality that doesn’t brag

Beyond appearance, a movement’s structure and choice of materials speak to its robustness.

- Regulating organ: a variable-inertia balance (with screws or weights) favours long-term stability over a simple index regulator. A silicon hairspring or an anti-magnetic alloy improves resistance to magnetic fields and corrosion.

- Shock protection: Incabloc, KIF or equivalents protect the balance staff. Their presence—and their quality—matters on an everyday watch.

- Frequency and torque: 4 Hz (28,800 vph) offers a smoother seconds sweep and good positional performance; 3 Hz (21,600 vph) can favour autonomy. What matters most is isochronism (rate consistency across the entire power reserve), not frequency alone.

- Rotor and winding: ceramic ball bearings, controlled lubrication, well-designed bi-directional or uni-directional winding. A very free-spinning, noisy rotor isn’t necessarily a flaw (the “wobble” of a 7750 is a classic), but winding efficiency must be there.

- Number of jewels: a reliable automatic calibre often sits between 24 and 31 jewels. Beyond that, beware decorative inflation.

Accuracy and regulation: the chronometer’s truth

A mechanical movement is alive; quality is measured by its ability to keep good time—everywhere, and for a long time. Proper regulation is essential to guarantee that precision.

- Certifications: COSC (-4/+6 s/day), METAS (0/+5 s/day and enhanced anti-magnetism), historic observatories… Certification isn’t mandatory, but it provides a framework.

- Positional adjustment: a good calibre is adjusted in several positions (at least 4, often 5 or 6). That’s where everyday consistency is won.

- Amplitude and beat: at full wind, a healthy amplitude typically sits between 270° and 310°. A low beat error reflects careful regulation.

- Stability over time: long-term accuracy is tied to lubrication, material quality, and the care taken in assembly.

Ask for numbers, not slogans: stated tolerances, positional adjustment, and whether the watch is put on a timing machine at the point of sale or during service.

Automatic winding efficiency: the heart that recharges

An automatic mechanical movement should wind quickly on the wrist, without wasting energy.

- Winding architecture: pawl systems (the “Magic Lever” type) or reversing-gear trains—each solution has its virtues. What matters is the efficiency and reliability of the reversers.

- Sliding bridle: prevents overwinding the mainspring. Essential, but its quality influences wear.

- Power reserve: 38 to 45 hours used to be the norm; 60 to 72 hours is becoming common. More isn’t always better if torque collapses at the end of the reserve: watch the isochronism.

Serviceability and the calibre’s pedigree

A quality movement is also a serviceable movement. A calibre’s nobility is measured by its ability to make it through decades.

- Parts availability: spare-parts networks, documentation, watchmaker training. A well-known industrial calibre (ETA, Sellita, Miyota, Seiko) is reassuring for maintenance; a serious “manufacture” must offer the same long-term support.

- Clear architecture: accessible bridges, well-integrated modules. An integrated chronograph differs from a module stacked onto a three-hander: neither is inherently bad, but transparency about the architecture matters.

- Lineage: a movement with a proven lineage (historic “tractor” workhorses, or newcomers designed with rigour) inspires confidence.

False friends to avoid

Spectacular skeletonisation doesn’t guarantee quality; it can even complicate legibility and stability. A cut-out rotor is no substitute for proper regulation. A tungsten mass won’t make up for poorly designed winding. Look for technical coherence, not showmanship.

Quick checklist before you fall in love

- Crisp finishing: clean anglage, regular Côtes de Genève, even perlage, flame-blued screws.

- Regulating organ: variable-inertia balance, anti-magnetic hairspring if possible.

- Shock protection present and well executed; rotor on a quality bearing.

- Clear stated accuracy, ideally with multi-position adjustment or certification.

- Sufficient power reserve and well-managed isochronism.

- A calibre with solid pedigree and parts available for servicing.

Between the lines: the calibre’s culture

Recognising a quality automatic movement is like learning an alphabet: anglage, stripes, amplitude, isochronism. It means accepting that virtuosity sometimes hides in the sobriety of a well-bevelled bridge, in the quiet of a rotor running smoothly on its bearings, in a seconds hand that doesn’t drift over an entire weekend. Fine mechanics isn’t a spectacle; it’s a conversation between time and the hand that tamed it. And on your wrist, it speaks of your taste for things well made—things that last—far from fashion and close to what matters.