This Watchmaking Complication Still Fascinates Collectors

The tourbillon, a miniature theatre that never grows old

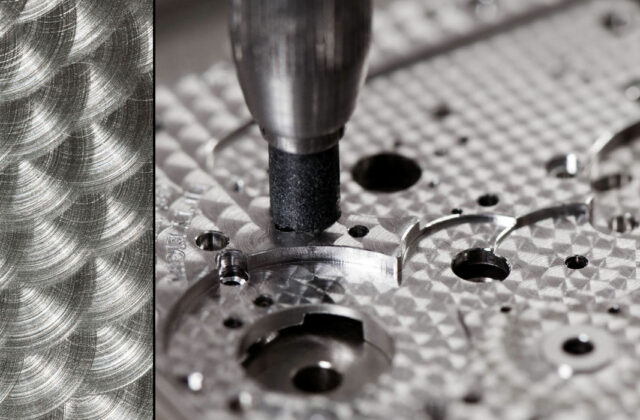

One glance is enough to understand: a rotating cage, a pulsing balance, flashes of mirror-polished steel. Here is a complication that hypnotises from the very first blink. The tourbillon belongs to that family of mad ideas which, in watchmaking, crossed the fine line between usefulness and pure culture. Two centuries after its birth, it remains one of the ultimate markers of savoir-faire—the fetish that tells a maison’s story, science and style.

An invention against gravity

Patented in 1801 by Abraham-Louis Breguet, the tourbillon was born of a very concrete problem: gravity disrupts the regulating organ of pocket watches, often carried vertically. By rotating the balance-spring and escapement within a cage (most often once per minute), Breguet hoped to average out rate errors and gain regularity. At the time, the observatory was judge and jury, and precision a competitive sport. The complication established itself as a tool of chronometry as much as an engineer’s signature.

From laboratory to legend

The 20th century changed the equation: the watch moved to the wrist, constantly changing positions and, paradoxically, calling less on the tourbillon for strictly chronometric reasons. But the idea did not disappear. In 1920, in Glashütte, Alfred Helwig imagined the “flying” tourbillon, freed of its upper bridge, as if suspended in mid-air—a gesture of architecture as much as watchmaking. Then, in 1986, Audemars Piguet launched the first serial production of an ultra-thin wristwatch tourbillon, marking the complication’s modern renaissance. From there, the story accelerates: Jaeger-LeCoultre would play tightrope-walker with its multi-axis Gyrotourbillon, Greubel Forsey would reinvent geometry with its inclined tourbillons, and high watchmaking as a whole would see in it a territory for expression.

- 1801: Breguet files the tourbillon patent.

- 1920: Alfred Helwig creates the “flying” tourbillon.

- 1986: back on the wrist, with an ultra-thin tourbillon produced in series.

- 2000s: creative explosion—multi-axis, inclined cages, modern materials.

Why collectors can’t get enough of it

If the complication still fascinates, it is first because it lays the mechanics bare. The tourbillon is not hidden; it is displayed at six o’clock, at noon, sometimes right in the centre. It is the watch’s “ballet”, the moment when crafts light up: hand-executed bevels, black polish on the cage arms, cambered forms, blued screws. Straight lines become washes of colour; curves seem alive. The object tells a story of hands, repeated gestures, patience. And this is where culture overtakes pure function: the tourbillon is a stage on which a maison expresses its aesthetic grammar and its mastery of long time.

- Mechanical theatre: a visible, narrative, almost cinematic complication.

- Maison signature: each cage architecture tells a style.

- High finishing: inspection under a loupe becomes an insider’s ritual.

- Controlled rarity: handwork, time invested, exacting standards.

Myth versus chronometric reality

The truth of observatory benches is not exactly that of the wrist. In motion, in multiple positions and sometimes equipped with modern materials (silicon hairspring, variable-inertia balance), a calibre without a tourbillon can compete with—or even surpass—a poorly adjusted tourbillon. But the myth is not built solely on a second gained: it rests on consistency in certain positions, on the difficulty of fine-tuning, on the intrinsic beauty of the solution. Modern competitions have shown it: tourbillons designed for performance remain formidable. The rest is alchemy between watchmaking and emotion.

Variations: when the tourbillon reinvents its dance

The vocabulary has expanded. Flying, double- or triple-axis, inclined at 30°, mounted on a remontoire d’égalité, paired with a fusée-and-chain, miniaturised for extra-thin cases: the complication has explored every path. Some prioritise expressiveness (the hypnotic multi-axis spherical cage), others performance (a calculated inclination to optimise the average across positions). Between the lines, the story continues: you can feel the workshop spirit, the search for the right compromise between spectacle and substance.

How to choose a tourbillon today

- Cage architecture: symmetry, lightness, controlled inertia (titanium, alloys).

- Genuine finishing: crisp bevels, sharp edges, black polish, coherent perlage and Côtes.

- Useful functions: tourbillon stop-seconds, seconds on the cage, a legible power reserve.

- Regulation: a quality hairspring (overcoil, stable materials), a balance with inertia weights.

- Frequency and autonomy: the balance between precision and endurance.

- Service and longevity: in-house know-how, access to parts, a clear warranty.

- Design language: the dial and the cage must converse, not ignore each other.

A good tourbillon is recognised by its coherence: beauty of gesture, rigour of construction, accuracy of narrative. It doesn’t need to overdo it; it needs to be right—and well done.

A few milestones to know

- The historic pocket-watch tourbillon: the complication’s roots, the observatory aesthetic.

- The first serially produced wristwatch tourbillon of the 1980s: proof the idea can live on the wrist.

- The “flying” tourbillon: a suspension that visually lightens the mechanics.

- Multi-axis and inclined: three-dimensional exploration, between kinetic art and the pursuit of regularity.

- The stop-seconds tourbillon: precision in the service of setting the time, a sign of contemporary thinking.

Beyond the complication, a culture

In a world saturated with screens, the tourbillon reminds us that beauty can be mechanical, that time has texture. It is not merely a complication: it is a living chapter in watchmaking history, a language shared by workshops and collectors, a ritual passed on. To watch it turn is to accept that the superfluous can reforge the essential: the intimate relationship we maintain with the object, the hand and time.

And that may be the secret of its fascination. The tourbillon no longer has to prove its usefulness; it proves something else, rarer: that engineering can be poetry, and that heritage, when worn well, never weighs you down. It elevates.