What Is a Watch with a Monobloc Case?

One piece, one idea: sealing time inside

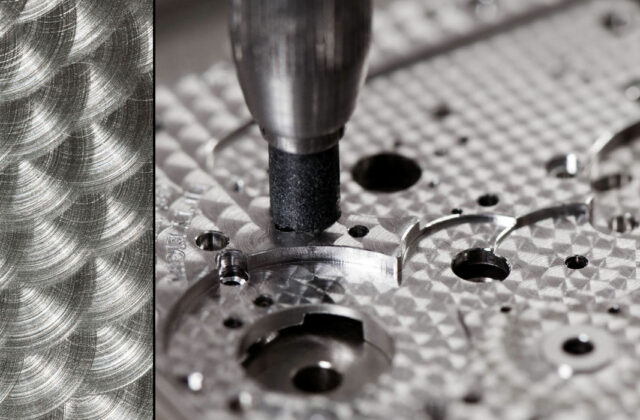

In watchmaking, some technical solutions read like manifestos. The one-piece case (or “monocoque”) is one of them. The principle is easy to state and far harder to execute: the case is no longer made with a screw-down or snap-on back, but from a single piece that forms both the middle case and the back. In other words, the rear of the watch isn’t a door: it’s a wall.

This architecture has an immediate, almost philosophical consequence: if you can’t open it from the back, you have to access the movement from the front (dial side). That demands a specific construction, mastery of assembly, and often a certain strength of character in the design. The one-piece case isn’t merely an engineer’s option; it’s a different way of thinking about the watch as an object—closer to a miniature safe than a jewellery box.

Definition: what exactly do we mean by a “one-piece case”?

A one-piece case is a case whose middle case and back are machined or formed as a single component. It therefore has no removable caseback. By contrast, the vast majority of contemporary watches use a back that is:

- screw-down (the most common on sporty, water-resistant timepieces),

- snap-on (often on dressier or vintage models),

- or more rarely secured by peripheral screws.

On a one-piece case, opening is generally done by removing the crystal (glass) and/or the bezel, then extracting the movement from the top. This constraint dictates the use of specific gaskets, internal retaining systems and, at times, multi-part or decoupling winding stems.

Why invent the one-piece case? The quest for water resistance

If the history of the one-piece case could be summed up in a single word, it would be: water resistance. Every opening is a potential weakness. A separate caseback means an additional sealing surface, the risk of improper closure, ageing gaskets, deformation, or water ingress after an impact.

By eliminating the caseback, you remove a major source of vulnerability. That idea appealed to utilitarian, military and dive watchmaking: fewer entry points, fewer problems. In the decades when modern diving became widespread and tool watches turned into instruments, the obsession with water resistance pushed many brands to explore radical routes: compression cases, protected crowns, oversized gaskets… and one-piece cases.

The logic is crystal clear: the strength of an integral shell, like a helmet, reassures engineer and wearer alike. It is also an answer to the real world: sand, salt, pressure changes, everyday knocks. The one-piece case is one of the purest expressions of this “use-driven” watchmaking.

How does it work day to day? Accessing the movement from the front

The detail that changes everything: servicing. On a conventional watch, the watchmaker opens the back, reaches the calibre, and works in relative comfort. On a one-piece case, everything happens from the dial side. That involves:

- removing the bezel and/or the crystal,

- possibly removing the dial and hands depending on the construction,

- more demanding procedures for the winding stem (sometimes in two parts, sometimes released via a discreet push-piece).

This need for “frontal surgery” has two consequences: first, it requires technical familiarity (and the right tools); second, it can make servicing more expensive. That doesn’t mean these watches are fragile—quite the opposite. But they remind us that watchmaking is the art of compromise: gaining water resistance can come at the cost of simpler maintenance.

The advantages: robustness, security, purity of line

Potentially superior water resistance

By removing one sealing surface, the one-piece case reduces a critical area. Of course, water resistance still depends on the condition of the gaskets, the crown, the crystal and the quality of assembly. But all else being equal, one less closure is often good news.

Better structural strength

A case cut from a single piece behaves like a shell. In the event of an impact, it can distribute stresses more effectively. It’s easy to see why this architecture appealed to watches designed to take a beating.

A more “monolithic” aesthetic

Some one-piece cases deliver a particular sensation: that of an object sculpted rather than assembled. Fewer separation lines, fewer breaks—visually, it can create a kind of technical elegance, an almost industrial restraint.

The limits: more complex servicing, constrained technical choices

Maintenance can be more delicate

Accessing the movement from the front means handling visible components (crystal, dial, hands). That can require more care and time, and therefore potentially higher service costs.

Design constraints

One-piece construction can influence:

- the shape of the rehaut and the internal architecture,

- the movement retention system,

- the kinematics of the winding stem,

- how a transparent back is integrated (often impossible on a “true” one-piece case).

If you enjoy admiring a calibre through a sapphire caseback, the one-piece case is generally not your best ally. By definition, it seals the watch like a safe, not like a display window.

One-piece, monocoque, “front-loading”: avoiding confusion

Terms get thrown around, sometimes incorrectly. A few useful reference points:

- One-piece / monocoque: the back and the middle case are one and the same.

- Front-loading: the movement is loaded from the front. Many one-piece cases are front-loading, but some non-one-piece watches can also be designed to be serviced from the front.

- Two-piece case: caseback + middle case (or middle case + specific bezel). That isn’t one-piece, even if water resistance can be excellent.

Vocabulary matters, because the appeal of the one-piece case lies precisely in eliminating an openable back. It’s a mechanical definition, not a marketing claim.

A tool-watch culture: when engineering tells the story of an era

The one-piece case evokes a time when a watch wasn’t merely an accessory, but a field instrument. It brings to mind timepieces that accompanied professions: divers, soldiers, engineers, explorers. An era when water resistance wasn’t a line on a spec sheet, but a condition for the mechanism’s survival.

What fascinates is that the solution is almost anti-glamour: adding spectacle (a transparent back, generous decoration) has no place here. The one-piece case prioritises function. And paradoxically, it’s precisely this refusal of easy appeal that gives it an aura today. In a world of objects optimised for the image, it recalls a kind of watchmaking optimised for reality.

Should you choose a watch with a one-piece case?

It all depends on your relationship with the watch. If you’re looking for:

- a genuine logic of robustness and protection,

- a less common watchmaking architecture,

- a more “block-like”, more integral design,

then a one-piece case makes sense. On the other hand, if you value easy servicing at any workshop, or the pleasure of contemplating the movement, a traditional case will suit you better.

Ultimately, the one-piece case is a choice with personality. It says something about its owner: a preference for technical coherence, for the idea that a watch can be conceived as a protective shell—a small bastion of steel (or titanium) against water, dust and time. And in that quiet radicalism lies a form of elegance: the kind that doesn’t try to seduce, but to endure.