What Is a Power Reserve and Why It Matters

There is, in the ritual of a mechanical watch, a poetry that defies time. In the morning, you adjust a crown, feel the resistance of the mainspring, almost listen to the silence of a mechanism coming back to life. Behind that simple gesture lies an essential notion—often cited on spec sheets but rarely explained with any nuance: power reserve. It tells you how long your watch will keep beating on its own before it stops. But it also says something about your relationship with the object: daily wear or a rotation of pieces, a quest for precision or absolute ease, fascination with high watchmaking or elegant pragmatism. For those wondering about the inner workings of these marvels, the automatic movement offers a fascinating perspective on the energy that drives every tick.

Power reserve: the definition, without the jargon

Power reserve corresponds to the autonomy of a mechanical (or automatic) watch once it has been fully wound. Put simply, it is the length of time during which the movement receives enough energy to run properly, before the mainspring relaxes to the point that the watch stops. To ensure this performance, the quality of the oils used in the mechanism plays a crucial role, guaranteeing optimal lubrication of the components.

It is most often expressed in hours: 38 h, 40 h, 70 h, 120 h… Some brands proudly display it on the dial (“Power Reserve”), others tuck it discreetly into the product sheet. Either way, it is an indicator of “energy capacity”: the amount of energy stored, the efficiency with which it is transmitted, and the way it is consumed by the escapement and regulating organ.

Two families: manual-winding and automatic

On a manual-winding watch, power reserve depends entirely on your action: you wind the crown, you charge the mainspring, and then the watch gradually draws on that energy.

On an automatic watch, the principle is the same, but energy is partly replenished by wrist motion via an oscillating weight (the rotor). An automatic watch can therefore “keep itself” above a certain level of charge if you wear it regularly. Set down on a table, however, it once again becomes a mechanism with finite autonomy.

What is a high power reserve really for?

You might think “more is better”. In reality, power reserve matters above all because it determines everyday comfort. A watch is a companion: it should follow your rhythm, not the other way around.

1) Getting through a weekend without thinking about it

The most telling scenario is Friday evening. You take your watch off, wear something else on Saturday, go out without a watch on Sunday, then put it back on Monday morning. A watch with a 38–42-hour power reserve will often have stopped. A watch with 70 hours, on the other hand, has a strong chance of still being alive—and, crucially, still on time.

2) A blessing for collectors

If you rotate several watches, a more generous power reserve saves you from resetting the time and date too often. It may sound anecdotal… until we start talking about complete calendars, moon phases or annual calendars. Some settings require method, and sometimes precautions (notably avoiding quick-set corrections close to the date change). A large power reserve then becomes a genuine convenience.

3) Stability and accuracy: not always, but sometimes

As the mainspring unwinds, the torque delivered to the movement varies. Depending on the calibre’s architecture, that variation can influence balance amplitude and therefore chronometric behaviour. Manufactures have spent decades working to smooth out these differences (optimised escapements, modern materials, specific barrels, devices such as hacking seconds, etc.).

Be careful, though: a longer power reserve does not automatically imply better accuracy. Everything depends on how energy is delivered and regulated, and on the overall quality of the movement.

How do you get 70, 100 or 120 hours of autonomy?

Extending power reserve isn’t simply a matter of “putting in a big spring”. It’s a balance between storage capacity, efficiency and consumption.

Barrel(s): the energy tank

The barrel houses the mainspring, the true reservoir. To increase autonomy, you can:

- Increase the size of the barrel (more room for the spring, more energy).

- Optimise the spring (alloys, geometry, more consistent torque curves).

- Multiply the barrels in series, to spread energy delivery and gain autonomy.

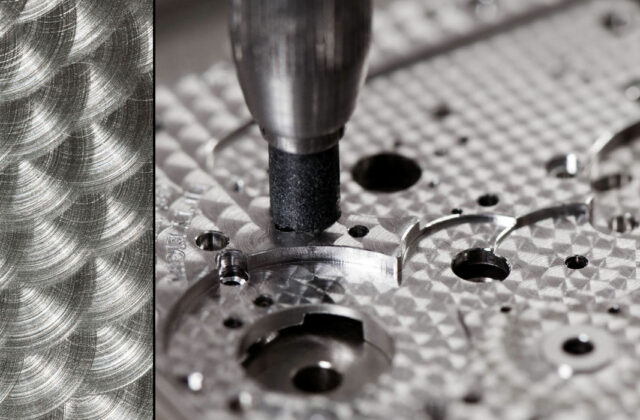

Efficiency and friction: watchmaking as a science of detail

A movement “consumes” energy because of friction and losses. Polishing, treatments, oil quality, jewel selection, gear-train architecture: everything matters. Improving efficiency can sometimes add hours of autonomy without increasing volume.

Frequency: the movement’s tempo

A high-frequency watch (for example 4 Hz and above, depending on the calibre) can offer better resistance to disturbances, but it often “eats” more energy. A high power reserve combined with a high frequency therefore demands a particularly efficient design (or more energy storage).

The power-reserve indicator: useful or a gimmick?

The power-reserve indicator (often a hand or an arc-shaped display) is not just a styling flourish. On a manual-wind watch, it prevents you from winding “blind” and reminds you that part of the object’s pleasure lies in its mechanics. On an automatic, it tells you the real level of charge—handy if you rotate watches or if your day-to-day life is very sedentary.

It is also a cultural sign: historically, this complication flourished on watches designed for reliability and energy management, notably in precision watchmaking and certain traditional pieces.

Power reserve and real-world use: what you’re not always told

The stated power reserve is generally measured under standard conditions, on a fully charged movement, until it stops. But between “still running” and “running at the best part of its torque curve”, there is sometimes a nuance. Some watches keep going even as their amplitude drops, which can affect accuracy at the end of the reserve.

Another point: an automatic watch worn on the wrist does not necessarily stay at 100% charge. If your activity is moderate, it may operate in a middle zone. Brands generally design for this, but it’s one more reason to view autonomy as comfort, not as a guarantee of absolute performance.

Which power reserve should you choose? A simple guide

For an “everyday” watch

- 40–50 hours: enough if you wear it daily and enjoy the ritual.

- 70 hours: an excellent comfort zone (Friday evening → Monday morning).

For a rotation of several watches

- 70–120 hours: ideal for limiting resets, especially with a date.

- Power-reserve indicator: strongly recommended if you’re juggling pieces.

For calendar complications

- High reserve: it can spare you tedious adjustments.

- Caution: if the watch stops, follow the correction instructions (the “forbidden” zone around the date change depending on the movement).

Which watch has the largest power reserve in the world?

As of now—if I may put it that way—the watch holding the record for the largest power reserve is the Vacheron Constantin Traditionnelle Twin Beat Perpetual Calendar with, believe it or not, 65 days of power reserve!

In addition to hours and minutes, it displays the date, month, leap year (obviously—it’s a “QP”) and its incredible power reserve. Its secret? You can slow the frequency of calibre 3610 QP, switching from high-frequency mode (5 Hz) to low-frequency mode (1.2 Hz) while maintaining good chronometric performance.

Final word: a technical notion, a very human luxury

Power reserve is not just a line on a spec sheet. It is a bridge between engineering and real life. It expresses a watch’s ability to adapt to your pace, your style, your habits. In a world where everything can be recharged at will, where time is displayed everywhere, the mechanical watch continues to exist through this form of controlled fragility: it lives on finite energy, which it turns into seconds—and stories.

And perhaps that’s where power reserve truly becomes important: not because it “gives you more”, but because it reminds you, with elegance, that time must be earned—and that a well-designed object knows how to fade into the background while still remaining present.

And if you really have far too many watches (I know the feeling…), use an automatic watch winder! You’ll find a small selection here.