Why Do Some Watches Have “Jumping” Seconds?

That intriguing “tick”: deadbeat seconds, a rhythm that’s not so anachronistic after all

You may have noticed it in a display window, or on the wrist of a collector friend: the seconds hand advances in crisp jumps, as if the watch were hesitating between two eras. In an age of mechanical movements that happily “glide” at 6, 8 or 10 beats per second, this perfectly jumping seconds display feels deliciously retro … and profoundly technical.

Because no, a jumping seconds hand isn’t necessarily the sign of a quartz watch (where the hand typically advances one step per second). In mechanical watchmaking, this complication very much exists. It answers a clear intention: to make the seconds easier to read, sometimes more “scientific”, and to offer that little piece of mechanical theatre that makes the difference between a simple display and a staging of time. Why keep it simple? And yes, that’s haute horlogerie too—haha.

Definition: what exactly do we mean by “deadbeat seconds”?

In watchmaking, we speak of deadbeat seconds when the seconds hand makes a clean step each second, rather than moving in an almost continuous sweep. Not to be confused with:

- The “sweeping” seconds (the most common on modern mechanical watches): the hand advances in micro-increments linked to the balance frequency.

- The quartz seconds hand: one jump per second, driven by a stepper motor, often associated with the famous “tick-tock”.

- The foudroyante (or “lightning” seconds): a high-frequency hand that can make one revolution per second, useful for reading fractions (1/8, 1/10, 1/100 depending on the case).

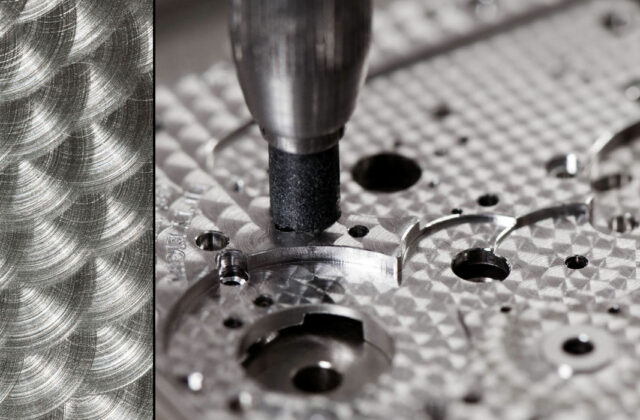

Mechanical deadbeat seconds are therefore a complication: they require a specific arrangement of wheels, levers and springs, designed to store and then release energy at regular intervals. In other words, the watch “prepares” the second … then triggers it.

This video from A. Lange & Söhne explains the complication in a very educational way:

Why invent deadbeat seconds when a “sweep” seems more noble?

The idea isn’t to imitate quartz. Historically, it’s quite the opposite: long before quartz popularised the jerky display, mechanical watchmaking explored deadbeat seconds for very practical reasons.

1) For legibility and measurement

A hand that jumps exactly from one marker to the next makes the seconds easier to read. In certain contexts—observation, navigation, timekeeping, medicine (taking a pulse), railway operations—this “visual” precision makes sense. Deadbeat seconds work like punctuation: each step is an event.

2) For the aesthetic of “discrete” time

Watchmaking time isn’t only a flow: it’s also a partitioning. Deadbeat seconds stage that idea with a particular elegance. The dial becomes a metronome, an instrument. It’s no longer fluidity that seduces, but cadence.

3) Because it’s a mechanical feat

Making a hand “jump” at precisely the right moment, without disturbing the movement’s isochronism or draining the power reserve, is an exercise in architecture. As so often in haute horlogerie, the interest lies as much in the result as in the way it is achieved.

How it works: the mechanics behind the jump

Without getting into a watchmaking-school diagram, let’s keep the essentials in mind: mechanical deadbeat seconds generally rely on an accumulating element and a triggering element.

The principle: accumulate, then release

The automatic movement draws a little energy from the gear train to tension a small spring (or charge an equivalent system). Over the course of one second, energy accumulates. Then, at exactly the right moment, a lever releases that energy in one go: the hand “jumps” by one index.

The constraints: stability, consumption and precision

- Energy consumption: each jump requires effort. If the system is poorly designed, the power reserve suffers.

- Rate stability: the trigger can create a micro-disturbance. The watchmaker must control it to prevent the balance amplitude from varying too much.

- Regularity: if accumulation or release is imperfect, you’ll get a “soft” or irregular jump—the sworn enemy of refinement.

This is precisely where the difference lies between an anecdotal deadbeat seconds display and a high-level one: the visual feel, the crispness of the step, the absence of tremor, and an impression of absolute control.

A point of vocabulary: “deadbeat seconds”, “seconde morte” and their nuances

In English-language watch literature, you’ll often come across deadbeat seconds. In French, the term is seconde morte, which is a bit misleading, since the watch is obviously very much alive. The expression refers to the idea of a second that seems to stop between two steps, rather than “creeping” along.

Depending on the construction, some deadbeat seconds are achieved via mechanisms akin to those used in regulators or historic precision watches. Others are more the result of a contemporary approach to mechanical design, conceived for visual pleasure.

Quartz vs mechanical: how not to get it wrong

The confusion is common: “If it jumps, it’s quartz.” Not necessarily. A few simple pointers for enthusiasts:

- The sound: quartz often produces a sharper tick-tock (but it’s not a universal rule; some cases dampen a lot).

- The dial: mechanical deadbeat seconds watches are often proud of the complication and may state it (wording such as “seconde morte”, “deadbeat seconds”, etc.), though not systematically.

- The hand behaviour: on a true mechanical deadbeat seconds, the jump can feel “firmer”, sometimes more precisely aligned, with a very crisp trigger.

- Price and positioning: integrating a properly executed mechanical deadbeat seconds is costly; if the watch is very affordable, chances are high it’s quartz (or a low-cost classic central seconds, but sweeping).

Why you don’t see it often: a “quiet” complication, but a demanding one

Deadbeat seconds are the perfect illustration of a complication that doesn’t “make noise” on a spec sheet, yet requires real engineering work. Many brands prefer to invest in more visible complications (chronograph, GMT, power reserve) or ones that are more immediately marketable.

Add to that a cultural logic: for decades, a smooth seconds hand has been associated with the nobility of mechanical watchmaking, while the one-second jump became, in the collective imagination, the distinguishing sign of the quartz and mechanical movement. Bringing deadbeat seconds back into the spotlight also means overturning a prejudice.

When deadbeat seconds become a style manifesto

On certain timepieces, deadbeat seconds are more than a function: they’re a signature. They speak of a kind of watchmaking that isn’t afraid to be cerebral, almost instrumental. A watchmaking that embraces time not as a ribbon, but as a sequence of decisions.

In a world where everything is continuous—the scroll, the streaming, the day that spills over—deadbeat seconds bring order back. They say: “Here is the second. And now, the next.” It’s minimalist, almost philosophical. And, paradoxically, very contemporary.

What to remember before you go looking for one

- Deadbeat seconds can be mechanical: it’s not the preserve of quartz.

- It’s a complication that requires a mechanism to store and release energy.

- It prioritises legibility and a rhythmic aesthetic of time.

- It’s rare because it’s demanding to execute without harming accuracy and autonomy.

The secret charm of the “step” in the march of time

You might think watchmaking swears only by fluidity. Yet some of the finest horological ideas are born from the opposite: interrupting, segmenting, setting a rhythm. Deadbeat seconds belong to that family. They don’t seek to mimic quartz; they remind us that mechanical watchmaking can also be precise, legible, and surprisingly modern in the way it displays the instant.

The next time you see a seconds hand advance in a crisp step, don’t jump to conclusions. Look closer: you may be looking at a discreet, almost confidential complication—a little plot twist, once per second.