How Quartz Watches Nearly Killed Swiss Watchmaking

The day precision became a weapon

Some revolutions arrive with trumpets blaring; others settle in as if self-evident, quietly, until the moment they flip the table. At the end of the 1960s, an innovation born in Japan and refined in laboratories around the world would shake the most prestigious edifice of the European industry: the quartz watch. More accurate, simpler to produce, more robust and markedly cheaper, it struck at the very heart of Switzerland’s value proposition: mechanical mastery, patiently perfected over centuries.

This technological shock—now known as the “quartz crisis”—nearly spelled the end of a craft. And yet it also triggered one of the most remarkable industrial and cultural rebirths of 20th-century watchmaking: that of a Switzerland that learned first to survive, then to triumph, by redefining what a quality watch is.

Before the quake: the golden age of Swiss mechanics

In the mid-20th century, Switzerland was the global benchmark. Manufactures and établisseurs supplied the planet with mechanical watches, from marine chronometers to elegant wristwatches. Accuracy improved, movements grew slimmer, reputations hardened. Owning a Swiss watch meant belonging to a certain idea of seriousness and style: genius miniaturised, to be worn every day.

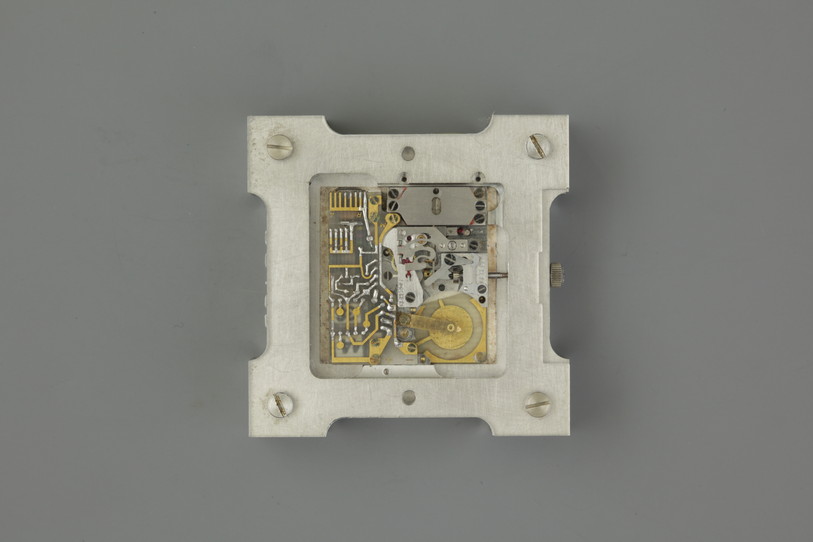

This dominance rested on an ecosystem: artisanal skills, a local supply chain, schools, a culture of complications and finishing. But it also rested, in hindsight, on a vulnerability: an industry built around a product that is costly to assemble, whose value is expressed through human effort and adjustment. Quartz, by contrast, is perfectly suited to the logic of consumer electronics.

Quartz: a silent revolution, then a tidal wave

Technically, the principle is crystal-clear: a quartz crystal, subjected to an electric current, vibrates at a stable frequency. Count those oscillations, convert them into impulses, and you get a level of accuracy that makes most mechanical watches of the era look ridiculous. Where a mechanical watch might drift by several seconds a day, a quartz watch drops to the order of a second… per month.

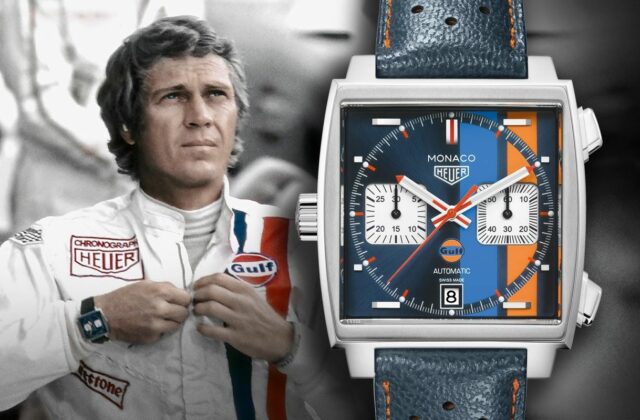

The symbolic date is often set at 1969, when Seiko launched the Astron 35SQ, the first commercially available quartz watch. Its price was high, but the message was unmistakable: the future has a printed circuit board. Costs soon fell, production industrialised, and the object became a modern product—desirable, rational, sometimes even futuristic in its design.

Why quartz was (almost) unbeatable

- Superior accuracy: more reliable day to day, less sensitive to position and shocks.

- Industrial-scale production: fewer manual adjustments, less highly skilled labour.

- Rapidly falling costs: electronics follow a steep learning curve, like all technologies.

- Simpler use: no winding, reduced maintenance.

Faced with such a cocktail, mechanical watchmaking suddenly looks old. Not noble: old. And in a decade obsessed with the idea of progress, that is an existential threat.

Switzerland caught off guard: when prestige is no longer enough

The irony is that Switzerland did not ignore quartz. The Centre électronique horloger (CEH) in Neuchâtel was working on prototypes as early as the 1960s, and several Swiss houses took part in the first breakthroughs. But the Swiss industry was fragmented, cautious, and deeply invested in mechanics. Innovation existed, but the industrial pivot came too late.

Meanwhile, Japanese players—followed by American and Hong Kong manufacturers—invested heavily, standardised, rationalised. Quartz became a global commodity. And when a technology becomes a commodity, it crushes anyone who thinks they can sell it at the price of prestige.

The consequences: an industrial haemorrhage

In the 1970s and early 1980s, Swiss watchmaking absorbed an immense social shock: closures, bankruptcies, forced consolidation. The figures vary depending on sources and the periods considered, but the trend is undeniable: Switzerland lost a substantial share of its watchmaking jobs and export volumes. The world did not stop wearing watches; it stopped buying Swiss watches—or bought only a minority of them.

The cultural misunderstanding: a watch is not just an instrument

Quartz won on the ground of efficiency. Yet the Swiss watch was never merely a utilitarian answer. It has always carried an imaginary: an object handed down, repaired, maintained; a mechanism that beats like a heart. But that imaginary was not told strongly enough, not claimed loudly enough, at the very moment electronics were redefining the notion of modernity itself.

This is what makes the quartz crisis so fascinating: it forced Switzerland to understand that its value is as cultural as it is technical. That a calibre is not only a solution for measuring time, but a way of inhabiting time.

The counterattack: consolidation, strategy, and the brilliant idea of Swatch

The revival came through industrial and strategic transformation. Faced with fragmentation, mergers accelerated and structures were streamlined. One name emerged as the symbol of the era: Nicolas G. Hayek, the architect of a restructuring that would lead to a new, more coherent powerhouse—able to invest and to defend itself.

But the most spectacular response was not a mechanical complication. It was a Swiss quartz watch… that embraced being a pop product—accessible, design-led: the Swatch, launched in the early 1980s. Plastic case, automated production, controlled costs, assertive style. Swatch does not deny quartz: it tames it, and turns it into an object of desire.

Why Swatch changed everything

- It reconciles Switzerland with quartz without renouncing national identity.

- It saves an industrial fabric by reviving volumes and margins in the mass-market segment.

- It reintroduces the watch as a cultural accessory: something you collect, match, and give as a gift.

The great return of mechanics: emotion as a counter-offensive

From the late 1980s—and especially in the 1990s—an unexpected phenomenon took hold: mechanical watchmaking became desirable again. Not because it was more accurate (it wasn’t) but because it was more expressive. Finishing, complications, brand histories, workshop gestures: Swiss watchmaking regained the upper hand by changing the playing field. Quartz won the battle of performance; Switzerland would win the battle of meaning.

It is also the moment when luxury is rediscovered as storytelling. A watch is no longer a simple practical object; it is a language: of elegance, heritage, and a certain permanence amid electronic obsolescence.

Two worlds, two promises

- Quartz: accuracy, simplicity, accessibility, pragmatism.

- Mechanics: emotion, craftsmanship, tradition, a desire for longevity.

The paradox is a beautiful one: without quartz, mechanics might never have been recognised for what it truly is—not the best solution for telling the time, but one of the finest ways to celebrate it.

What the quartz crisis still tells us today

In the age of smartphones and smartwatches, history is repeating itself in another form. Time is everywhere—free, synchronised. And yet mechanical watches continue to seduce, precisely because they offer something else: a presence, a ritual, a materiality. The quartz crisis nearly killed Swiss watchmaking, but it also forced it to understand its deepest singularity.

Ultimately, quartz did not “destroy” Switzerland; it compelled it to grow up. To distinguish the useful from the desirable, the product from the object, performance from soul. And that may be the most contemporary lesson of all: in a world where technology wins quickly, what endures is often what tells a story.