What Is the Lifespan of a Mainspring?

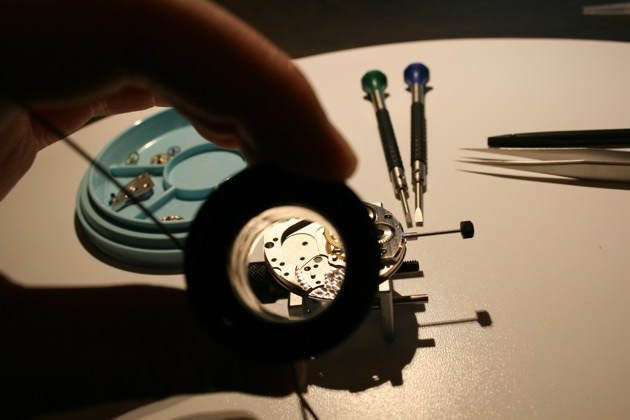

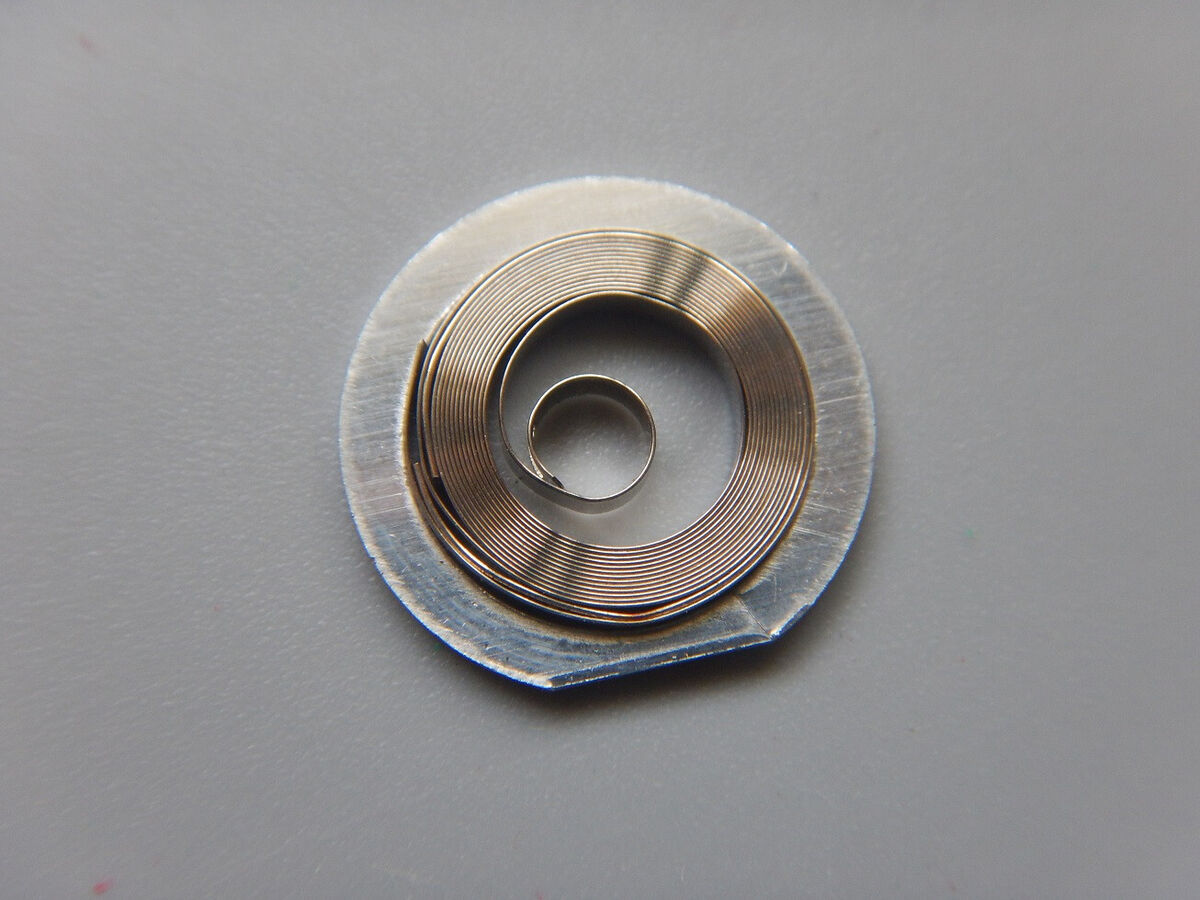

A Coiled Heart: Understanding the Mainspring

In a mechanical watch, the mainspring is more than just a component. It’s the invisible muscle, curled inside a slim steel drum—the barrel—that releases its energy with metronomic patience. Wind it and it tightens; let it unwind and the watch comes alive. A centuries-old ballet whose longevity fascinates as much as it raises questions.

So, how long does it last ?

The short answer: a modern mainspring can last for decades. The honest answer: its lifespan depends as much on what it’s made of as on how it’s treated—materials, usage rhythm, lubrication, movement design, environment. In practice, watchmakers recommend replacing it at every full service (every 5 to 10 years), not because it “dies” that quickly, but because it’s inexpensive compared with the benefits of consistent torque and restored reliability. To ensure that kind of durability, proper mechanical watch maintenance is essential.

From blued steel to modern alloys

The 20th century saw the traditional blued steel—known for “taking a set” (the spring “settles” and loses its punch)—give way to high-performance alloys: cobalt-nickel, iron-chromium-cobalt, and families such as Nivaflex or Spron. These “white” springs offer greater elasticity, better corrosion resistance, and more consistent stability over time. The result: less risk of breakage, a steadier power reserve, and a higher likelihood of making it through decades without faltering—provided the rest of the system keeps up.

The 5 factors that make the difference

- Use and winding cycles : a manual-wind watch goes through full daily cycles (fully wound → run down), whereas an automatic lives on continuous micro-cycles. Both are demanding in different ways, but modern alloys tolerate these stresses without drama.

- Barrel lubrication : greases and oils (including the famous wall grease for the slipping bridle) age, thicken, or evaporate. A dry barrel undermines smooth torque delivery, fatigues the spring, and can cause jerky running.

- Movement architecture : long power reserves, power-hungry complications (chronographs, big dates), or high torque loads put more strain on the spring. Multi-barrel calibres distribute the effort more effectively.

- Environment : shocks, humidity, and large temperature swings punish the barrel/spring assembly. Modern alloys resist magnetism better, but corrosion remains every metal’s enemy.

- Assembly and adjustment : a spring inserted incorrectly, a slipping bridle that’s too “greasy” or insufficiently braked, and performance is the first to suffer.

Automatic vs manual: which wears the spring more ?

A manual-wind watch is disciplined: you wind it fully, let it run down, once a day. An automatic, by contrast, lives to the rhythm of your movements, with a slipping bridle that skates along the barrel wall to prevent over-tension. In theory, the manual imposes more pronounced bending amplitudes; in practice, modern springs will take either for years. More often, the weak link isn’t the metal but the grease that serves it. For proper automatic watch setting, it’s essential to understand how these mechanisms work.

Signs it’s time to change the spring

- Power reserve in decline : the watch runs noticeably less long than stated, despite a full wind.

- Rough winding or unusual noises : crackling, jolts, a “gritty” feel—often a sign of exhausted lubrication, sometimes of a damaged spring.

- Amplitude variations : if, on the timing machine, amplitude collapses too quickly after a full wind, the torque being delivered is no longer healthy.

- Sudden stoppages : especially on a manual-wind, after an effort. The spring may be broken or the bridle faulty.

- An old watch left unused for years : with vintage pieces, older steel may have taken a “set”; bringing it back to life deserves a fresh spring.

Best practices to extend its life

- Stick to service intervals : 5 to 7 years with regular wear is a solid baseline. Open it up, clean it, re-lubricate, replace the spring.

- Avoid extremes : heat, humidity, or violent shocks degrade the barrel and lubricants long before they reach the spring.

- Measured winding : on an automatic, 15 to 25 turns of the crown are enough after a period of rest; there’s no need to overdo it.

- Storage : for extended downtime, let the watch run down naturally rather than keeping it constantly wound in a safe.

- Trust the test bench : measured amplitude, rate drift, and power reserve are worth more than impressions gleaned by ear.

And what about vintage ?

The charm of a calibre from the 1940s–60s also comes with the reality of its metals. Period mainsprings, in blued steel, break more readily and lose their snap. Replacing them with a modern alloy restores breath and power reserve, often without betraying the aesthetics or integrity of the piece. For purists, keeping the original is a collector’s choice; for wearers, the security of a fresh spring is a discreet but decisive luxury.

How much does it cost, and is it automatic ?

On a common movement, a new mainspring remains one of the most affordable parts on the bench: a few dozen euros for the part, included in the estimate for a full service. On rare, old, or proprietary calibres, availability sets the price. Automatic? Let’s say reasonably automatic: the improvement in torque stability and power reserve alone justifies preventive replacement.

Verdict: a marathon runner, not a sprinter

A modern mainspring, properly maintained, will outlast several straps and plenty of trends. Expect decades of potential service, but keep in mind that maintenance sets the tempo. Watchmaking, after all, isn’t only about seconds: it’s a discipline of consistency. And the spring, discreetly, is its most faithful craftsman.