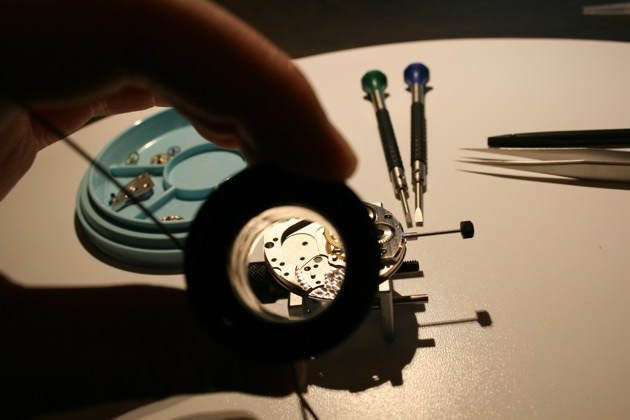

What Is a “High-Frequency” Movement in Watchmaking?

Definition: what do we mean by a “high-frequency” movement?

In watchmaking terms, frequency expresses the number of oscillations of the balance per second (measured in Hertz, Hz). The contemporary standard for a mechanical watch sits at 4 Hz, i.e. 28,800 vibrations per hour (vph). We speak of “high frequency” as soon as this threshold is exceeded—typically at 5 Hz (36,000 vph) and beyond. Some experimental creations climb to 10 Hz (72,000 vph) and even higher for chronographs with separate regulating organs.

In practical terms, the higher the frequency, the faster the movement “beats”. The tick-tock tightens up, the seconds hand glides with an almost hypnotic smoothness, and the watch becomes theoretically more stable in the face of life’s small day-to-day disturbances. Not to be confused with the electronic world: a 5 Hz mechanical calibre has nothing to do with an Accutron tuning fork (360 Hz) or quartz (32,768 Hz). Here, everything plays out in the nobility of the mainspring, the balance and the escapement—evidence of a mastered architecture.

A story of competition and engineers

The 1960s saw the birth of a genuine race towards high frequency. Girard-Perregaux led the way with its Gyromatic HF, followed by Longines and the Ultra‑Chron (1967).

Then, in 1969, Zenith made a statement: El Primero, the first integrated automatic chronograph at 5 Hz, capable of displaying tenths of a second. On the other side of the globe, Seiko and its 45KS and 61GS “Hi-Beat” refined Japanese precision at 36,000 vph.

The quartz crisis would bring this fervour to a halt, but high frequency was reborn in the 21st century, carried by materials science. Silicon reduces friction; new lubricants push back wear. Grand Seiko launched its 9S85 (then the 9SA5), Zenith modernised its iconic El Primero, Breguet unveiled the Classique Chronométrie 7727 at 10 Hz, and TAG Heuer reinvented time measurement with high-frequency chronographs that separate the timekeeping organ from the chronograph organ (Mikrograph at 50 Hz, then Mikrotimer).

Why high frequency changes the game

The goal is simple: to better “average out” errors. A balance that beats faster is less disturbed by a sudden shock or a slight variation in torque. Timekeeping becomes more stable, especially on the wrist—far from the ideal conditions of an observatory chronometer.

- Potentially higher accuracy: multiplying vibrations smooths out micro-deviations.

- Stability in real-world use: better resistance to disturbances and positional variations.

- Sporty legibility: at 5 Hz, a chronograph can legitimately display tenths of a second in mechanical terms.

- Aesthetics in motion: a smoother seconds hand, a more subdued beat.

That said, nuance is essential. Accuracy does not depend on frequency alone. It is the meeting point of a mastered architecture, excellent isochronism, fine regulation and the finishing of parts working in harmony. High frequency is a powerful tool—not a magic wand.

The technical trade-offs

Making a movement beat faster doesn’t come for free. Mechanics, for their part, present the bill.

- Energy consumption: the balance needs more impulses; power reserve can suffer.

- Wear and lubrication: more friction, therefore higher demands on materials, oils and maintenance.

- Demanding adjustment: maintaining comfortable amplitude and good isochronism at 5 Hz requires expert hands.

- Higher costs: specific components (silicon escapement, special alloys), highly specialised development.

Modern solutions mitigate these limits. The use of silicon (pallet fork, escape wheel, hairspring), magnetic pivots (at Breguet), or monolithic oscillators (developed by Zenith in its Defy lineage) reduces losses and stabilises the rate. Grand Seiko, with the 9SA5, proves that a 5 Hz can combine high frequency and a long power reserve (80 hours) thanks to an optimised architecture and a double-impulse escapement.

Iconic high-frequency watches and calibres

- Zenith El Primero (36,000 vph): the historic 5 Hz benchmark, from the period A386 to contemporary Chronomaster models displaying tenths of a second.

- Longines Ultra‑Chron (36,000 vph): a 1960s pioneer, recently relaunched with a contemporary approach to precision.

- Grand Seiko Hi‑Beat 9S85 and 9SA5 (36,000 vph): the Japanese school of consistency, superlative finishing and everyday accuracy.

- Breguet Classique Chronométrie 7727 (10 Hz): technical virtuosity, silicon escapement and magnetised pivots to tame 72,000 vph.

- Girard‑Perregaux Gyromatic HF (36,000 vph): an important chapter in the history of serially produced chronometers of the 1960s.

- TAG Heuer Mikrograph (50 Hz for the chronograph): separation of organs, 1/100th display, a manifesto of sporting engineering.

How to recognise a “high-frequency” watch

- Technical indication: “36,000 vph”, “5 Hz”, “Hi‑Beat” on the dial or caseback.

- Tenth-of-a-second chronograph: a dedicated scale and a central seconds hand that races from one marker to the next in a single second.

- Visual impression: a seconds hand smoother than a 3 Hz, without reaching the continuity of quartz.

- Sound: the tick-tock tightens up; trained ears can hear it.

For which enthusiast?

High frequency appeals to those who love lived precision, not merely certified precision. Collectors will find a slice of history—from yesterday’s observatories to today’s materials laboratories. Daily wear gains in peace of mind, provided one accepts sometimes more exacting servicing and a higher technical cost.

The elegance of an unapologetic beat

Choosing a high-frequency movement is to prefer a lively beat to a slow rumble, the determination of a metronome to the caress of long time. It is neither better nor worse: it is a temperament. Between an El Primero that slices tenths like a samurai master, and a 10 Hz Breguet that whispers science beneath a veneer of classicism, high frequency embodies watchmaking with character—where culture, engineering and style move forward in unison.